4 "Dumb" Design Ideas That Should Exist by Matt Chmiel

Plucked from the Cutting Room floor: 4 “Dumb” Design Ideas That Should Exist

By Matt Chmiel, Associate Director of Creative Strategy, Code and Theory

Code and Theory products help redefine how the digital world works and set new user-expectations for digital functionality. The undercurrent that drives all of our work is an open mind and a dedicated creative strategy process that insists on, and cultivates, the tongue-tied ideas that linger within our teams. After 18 years, our cutting room floor has PILES of dumb ideas. We love dumb ideas. Let’s celebrate some here…

Below are four ideas and concepts and four failed pitch stories about them. It does not matter that we’ve unsuccessfully pitched these ideas in otherwise successful projects; our failures to successfully persuade our partners makes these ideas gnaw at our collective dreams like little tiny beavers. They hibernate when we’re in the thick of a project and sneak out of their dens every time we have a new brainstorm session. These ideas require new dimensions of design and product thinking that take inspiration from unexpected sources and inject fresh ingredients into the well-worn design process. Developing these concepts demands bold thinking from the whole team: project management, product design, editorial, development, analytics and data, QA, and business units will all be challenged and motivated to contribute. We can’t quit these ideas because they represent a significant change, an evolutionary leap, a paradigm shift, and you have to know about them too.

1) Microsoft’s Clippy was good

We can hear your groans. Its name triggers instant feelings for anyone alive and conscious and digitally active in 1997. Clippy was successful because it made you feel something — irritation/rage/appreciation/delight — and that feeling gave the concept a theme, and that theme gave Clippy a future. Clippy personalized the anodyne digital experience; it was the progenitor of Alexa and Siri. That is impressive!

We believe that some kinds of publishers and high volume content marketing sites could use a Clippy. Before we proceed with an explanation, please feel free to sigh and preemptively reject this idea as ridiculously dumb or old; we’ll wait…

The new Clippy needs less technology and more personality. The first Clippy tried and failed to read your mind with a crude and generic taxonomy. Typing “To Whom It May Concern” triggered an “are you trying to write a letter?” This suggestion is not a feature as much as it is an unwelcome pop-up dialogue. There is a growing trend of digital assistants that follow this utilitarian track. The new Clippy we’ve proposed would act differently because it would not solve your problems or read your mind; it is not a technical marvel as much as a dynamic personality that behaves in its self-interest. Note that this is where the idea gets strange; we are now talking about feature behavior and not functionality. This vision for Clippy is more like a Tamagotchi than a Siri. We are talking about characteristics more than artificial intelligence. Designing the new Clippy is more like writing a character in a script than creating an interactive feature. This idea needs screenwriters more than it needs UX designers.

Our Failed Pitch Story:

We’ve pitched this concept several times. The initial reaction brings the beaver bite back… they love it. In one case, we were briefed to create a digital media destination that shattered digital norms — Joshua Topolsky’s The Outline. We were encouraged to introduce divergent and outlandish ideas to The Outline team and this idea generated the most serious deliberation. In this instance, the technical requirements of this character would have delayed the product launch which was an unacceptable business risk for many extremely logical reasons. Despite that pressure, they still considered it! In other cases and projects, the management of this kind of character is not an easy baton for the client to pick up as soon as our creative engagement ends. There needs to be a clear and passionate owner on the client-side who is eager to manage the feature through the roll-out and evolution of the character. This owner must persistently evangelize the benefit of this character before the grinding forces of inertia intervene and restore the same patterns that define a web experience today. Those patterns have no clear space for a Clippy — that will be the sentiment shared and expressed in the roll-out phases and through the initial rejection of new thinking that comes with this kind of launch. It is hard to insert a new thing into an established pattern. We get it!

2) Cultivate (a little) confusion

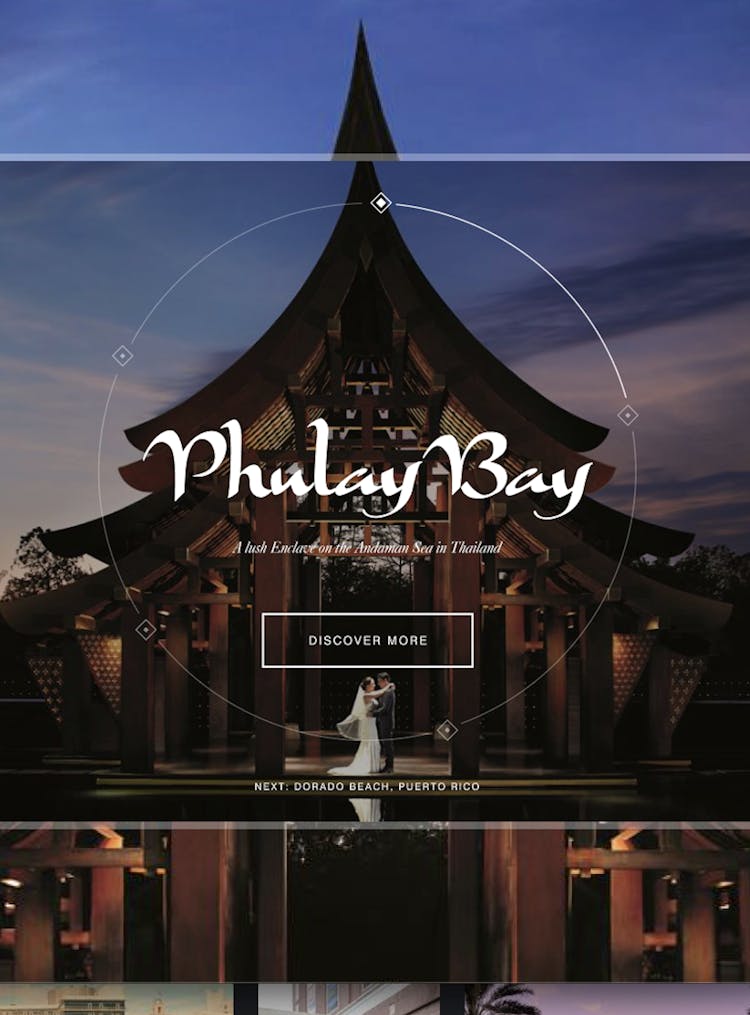

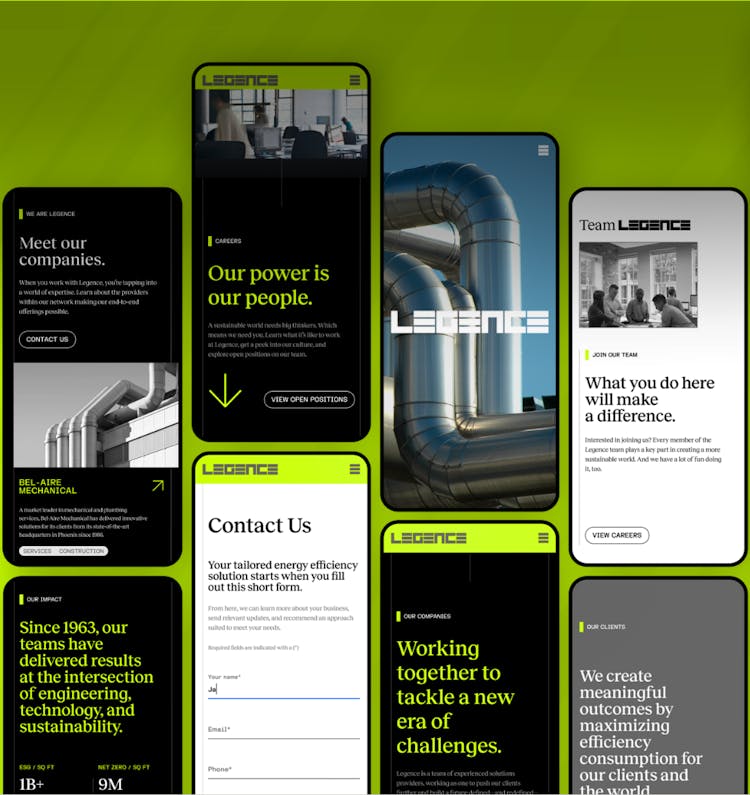

Every new website looks like it was built on the same platform and with the same building blocks. They all look clean and bright and efficiently laid out. This style is the ultimate triumph of user-centered design — something we believe in and integrate into our work as well — but it comes with a price. The problem with this phenomenon is that all this “good” design is homogenizing experiences. The antidote to that issue is just a little bit of dirt.

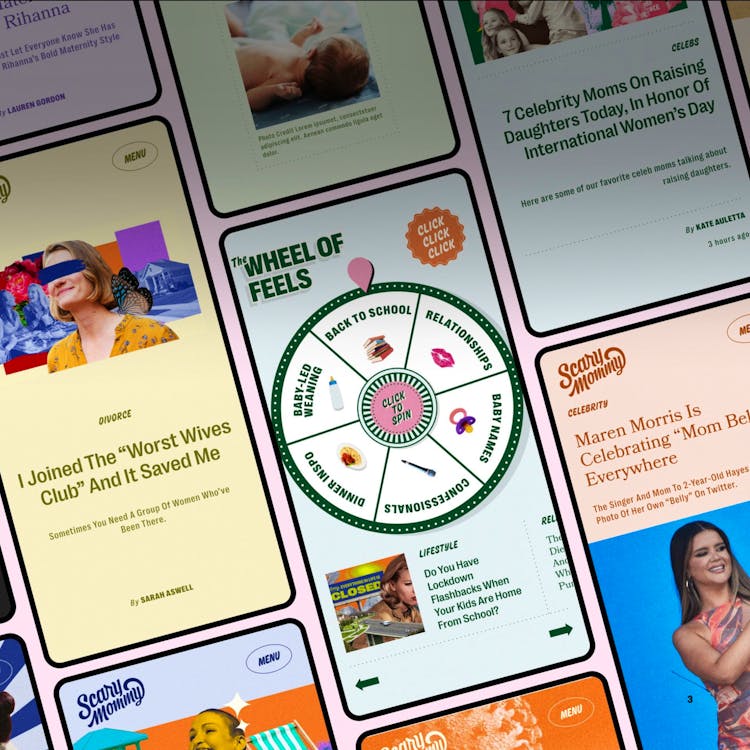

Our idea is to dedicate design thinking to defining and creating confusing digital experiences. It takes effort and precision to build confusing experiences without alienating an audience. Doing this well means we are transmogrifying confusion into a mystery. In a mystery, every little breadcrumb of clarity inspires the user to go one step deeper. A good kind of confusion is like an impossible video game — every failure inspires one more try. In both scenarios, the user is intently engaged and focused and at their most valuable. There are ways to do this, and we want to build them into some experiences.

Designing mysterious confusion into a digital experience is a conversation that almost NEVER happens in the design process. Our clients rightly expect our product to efficiently deliver its value to the user and to the bottom line — we will never compromise on that score. Nevertheless, we see a quantifiable value in curating high-engaging differentiated experiences that pique curiosity and help differentiate the product. Properly executed confusion will see more time on site, more click throughs, more messaging, and more social reflections (screenshot exclamations and open-questions like “how do I…), and repeat visits.

Our Failed Pitch Story:

We recently launched a new marketing platform for the MIT Sloan School of Management which featured a simple text messaging component. This simple box animates a single message on top of every page on the site — so far this is not confusing at all! The object of this text box is to give their internal page owner an opportunity to tell their audience the one thing that matters more than anything else. If that owner wanted its page visitor to know one thing, this box clearly delivers that message. So far, there are no beavers; we get it. Just wait: imagine visiting the home page of the school on March 14 (3/14) and seeing an illegible tangle of numbers auto-typing the first 15 digits of pi. A closer look at that line of text reveals that one of the digits, let’s say the 5, is a barely-concealed URL that links to a 404-type banner page. The whole experience plays out like a treasure-map breadcrumb journey that can culminate in a secret offline event or spectacle, like free pie slices in room 314 of building X. We presented this concept because of the school’s well-known affinity for celebrating that day; it was presented as MIT Sloan’s version of a google-doodle; transforming a simple sketch into a real-world experience that is driven by fun digital messages. When sharing the simple page-top text messaging component, we wrote a document full of storytelling examples that pushed the client away from utility messages and towards a little bit of interesting confusion. Post launch we notice with gleeful pride that our client is experimenting with exciting messages in that component and hope one day to find a truly unexpected message on top of one of their pages.

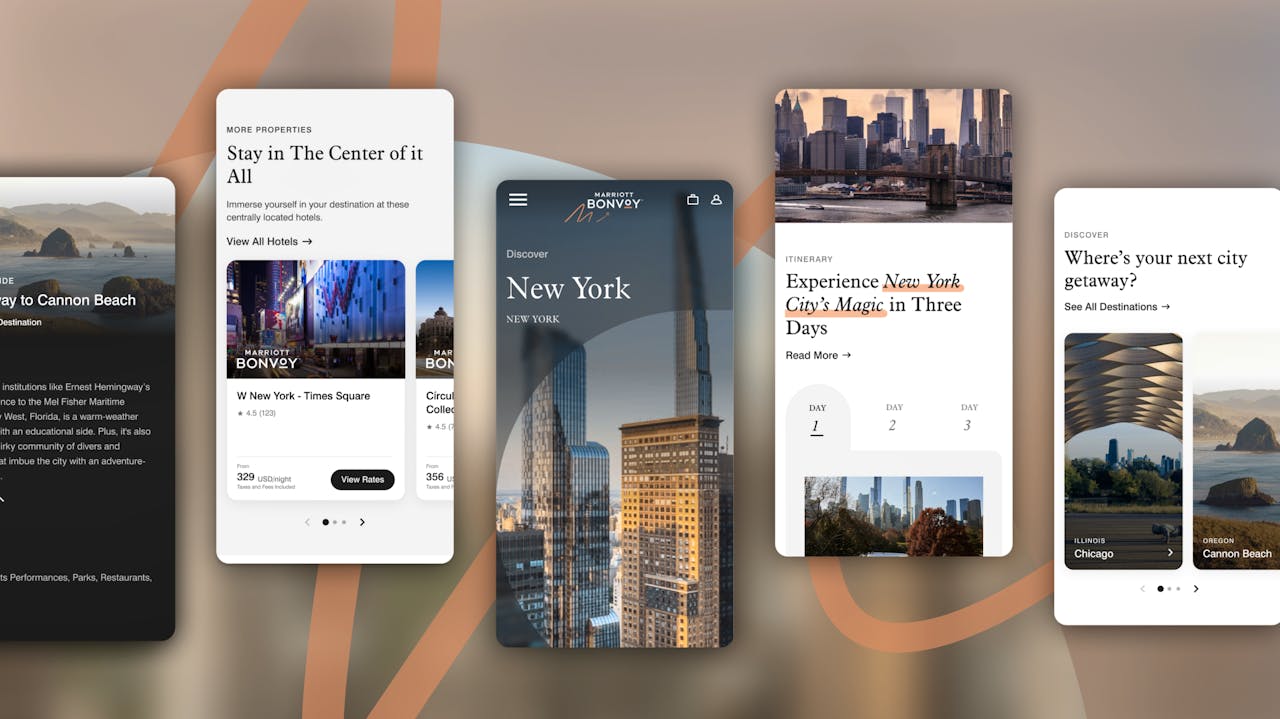

3) Copy radio stations

We have always wanted to design a live broadcast experience for a non-breaking news day. There are no media publication sites that do this in a way that we will describe it; the only comparative model we’ve ever seen exists at every radio station. Radio stations hire DJs to communicate directly to their audience: a DJ plays a song, delivers the weather report, lures listeners to call-in for on-air conversations and contests, reads ad copy, and engages in constant, reliable, meandering banter. Above all other things, a DJ is a crusader against dead air, going to desperate lengths to keep the audience engaged — “Don’t touch that dial, in 5 minutes we’ll get the ‘Led Out.” DJs constantly keep the listener updated about the program, like text-bubble typing dots (…), they keep the listener thirsty for one more update.

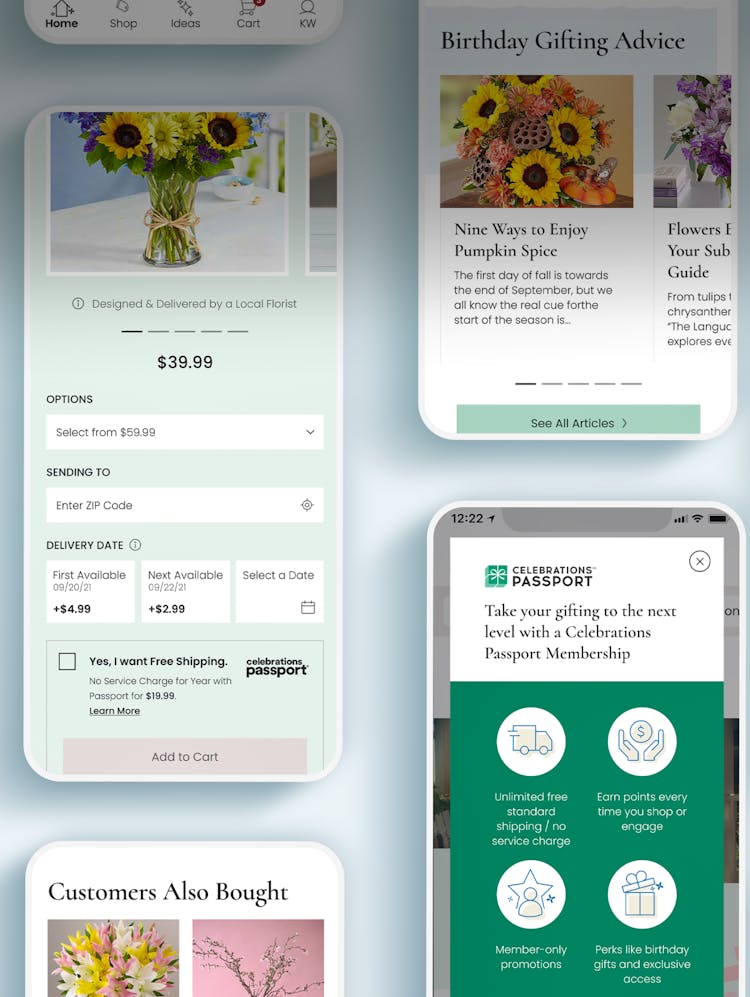

A high volume media website can do the same thing with text. This job is new and it needs a title so we’ll call it an EJ — an editorial jockey. A site could assign several of its prominent writers to time slots to actively broadcast messages that take over the home page. The parameters of this assignment follow closely with a radio DJ — each shift is 4 hours long and the assigned/active EJ has to communicate something to the audience on the home page at least once every 4 minutes. The EJ assignments would follow similar personality profiles of radio DJ’s — the most engaging, active, loud personalities take the morning rush hour slots, and the other types of personalities get other time slots that match different audience profiles. As with the radio DJ, the messages an EJ can send are various: calling out good comments from multiple articles, delivering an ad, promoting a new piece or an old but trending article, and directly messaging the audience to do one thing or the other. In this vision, the EJ turns the home page into a rich-media radio station that can keep its audience visiting and re-visiting the site again.

Our Failed Pitch Story:

We have pitched this concept a few times in the past. It is a very big experiment. In one project, a long time ago, we secretly produced some alternative home pages that demonstrate this feature in action. This concept was shared with Hearst magazine digital editors. We positioned the concept like a left-field alternative crazy idea and were met with painfully hopeful consideration. There goes those beaver teeth. There was real interest in this concept but the scale of change provoked an understandable reticence. We were pushing the scope of the project far outside the original bounds of the brief. For a time it was welcome but the approaching launch day brought it back down to normalcy. This idea requires tectonic change: new formats of writing, new real-time analytics operations, new ad-serving processes, and a new custom back-end interface. On top of all that, it would have taken a lot of pre-launch time, effort, and resources to practice and fail and ultimately figure it out how to combine all of those operations into a compelling experience. This is not a standard redesign effort; how many new media websites need extensive dress rehearsals?

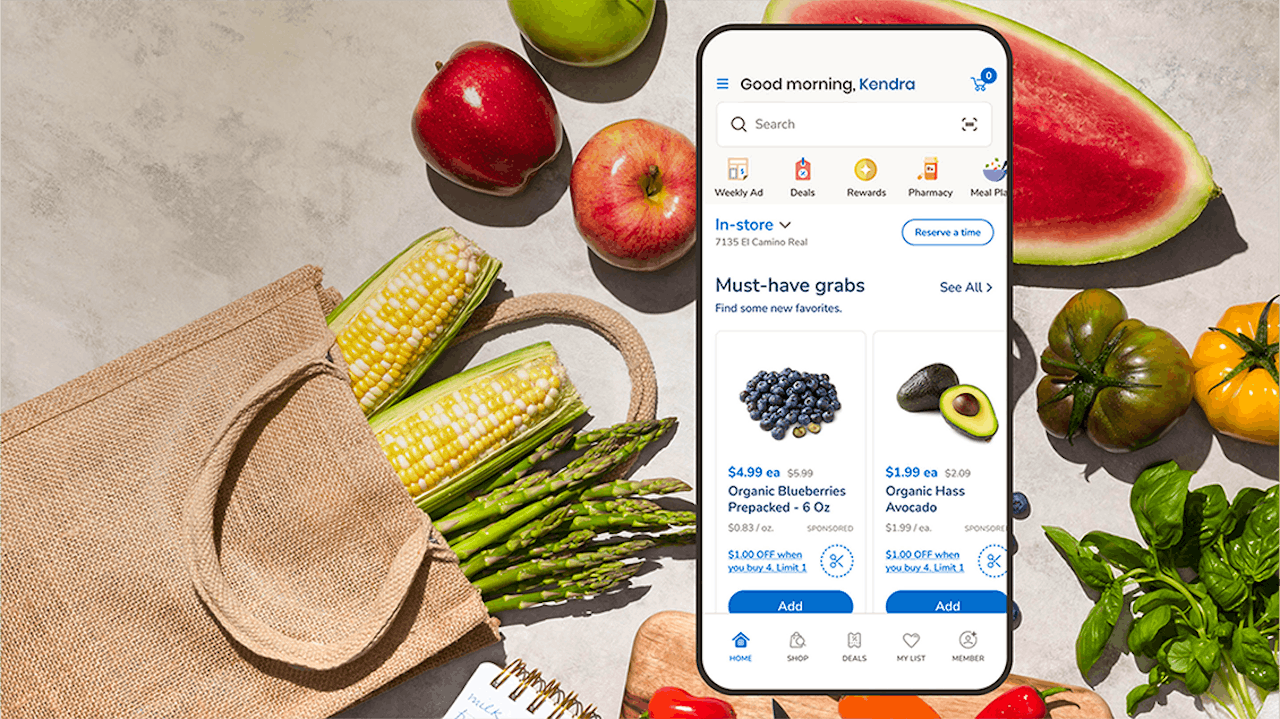

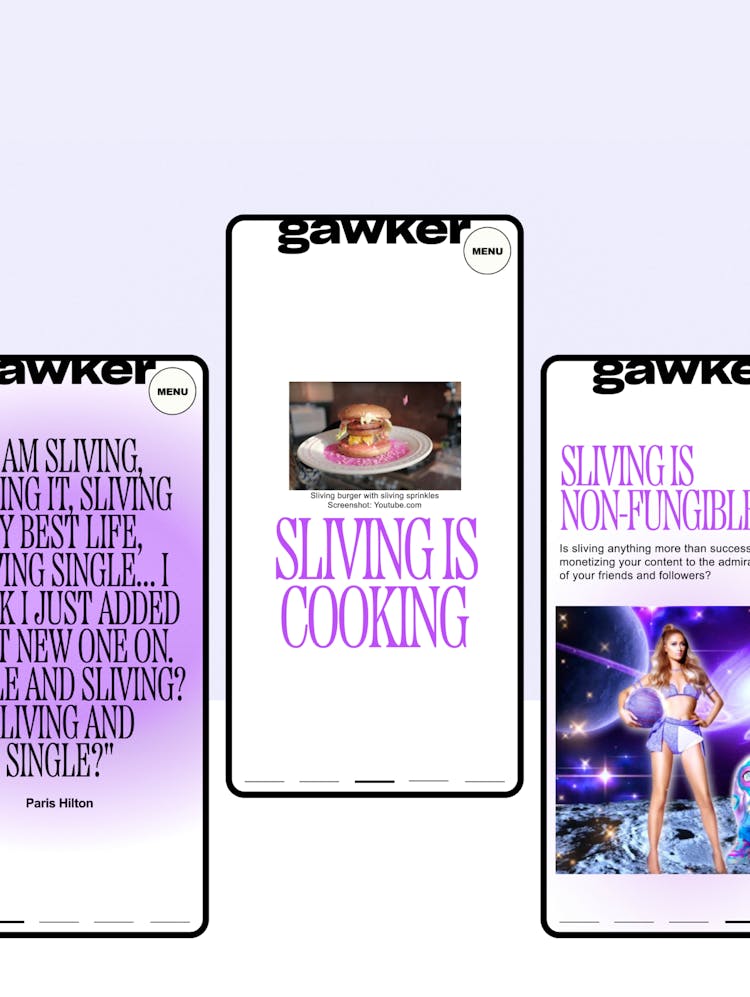

4) Cover comments like a reportorial beat

What would it look like if a high volume content site reported on its comments the same way it covers its other topical beats? We are envisioning a new role in this feature — a community ombudsman position. This person is like the Studs Terkel of comment sections: every day they hitchhike through the comment sections on the site to highlight trending sentiments and questions, promote exceptional individuals and stories, and drive attention to the meaningful audience actions. The ombudsman would do many things on the platform: sprinkle comments throughout the comment threads, publish weekly comment section reports, and occasionally take over during viral moments. This idea treats the community’s reaction to the publication’s content as source material for more content.

The biggest version of this feature is the article takeover. Imagine that an opinion piece is published on Monday morning with open comments. By Tuesday morning, the ombudsman identifies a trend of questions from the comments and then issues a response to the op-ed and promotes it on the home page. This piece is titled “The Community Wants to Know…” and goes on to describe the most important questions that the community of readers wants to the original author to answer. The author can then respond to the audience questions in a follow-up post. The ombudsman can then poll the audience to see if the question was adequately addressed. We imagine that the authors of these pieces will not appreciate the scrutiny. One of the intriguing elements of this feature is that it instigates friction and conflict into the platform which we think will facilitate a deeper relationship between the audience and the brand.

Our Failed Pitch Story:

This concept has been discussed but never formally pitched. The closest we ever got with a client turned into several weeks of consideration and back-channel resource planning. Ultimately it was scrapped because the concept requires a new role that does not exist and has no clear comparative model. It takes resources away from existing positions and invests it in an experiment that could fail. And so it goes back to the cutting room floor to gnaw some more, that little tiny beaver. We will wait until the next viable opportunity. Some day maybe soon.

Conclusion

An idea isn’t really fun unless it makes us feel a little bit vulnerable and dumb. Among many other reasons, we work here because we found a safe space to explore the uncharted territories of our ideas. These ideas come from every team within the organization and from our amazing clients. While coming up with new concepts is fun in its own right, the real benefits come when we all collaborate to make these features happen in real life. The follow-through on these concepts require new types of user-journeys to design against; that exploration will dislodge a new set of assumptions that can open up other ideas that we haven’t even considered yet. We know we’re aiming in the right direction when we find that there are no existing online interfaces that we can leverage and repurpose in order to deliver them. This means there are no existing editorial style guides that can help writers know how to write for these features and no obvious technical solutions that won’t require some creative problem solving. The benefits extend to every discipline in the organization. That sounds like the fun kind of challenge that gets people motivated and inspired. The best part is that these four ideas lie on a crested hill that is a pathway to a new horizon.